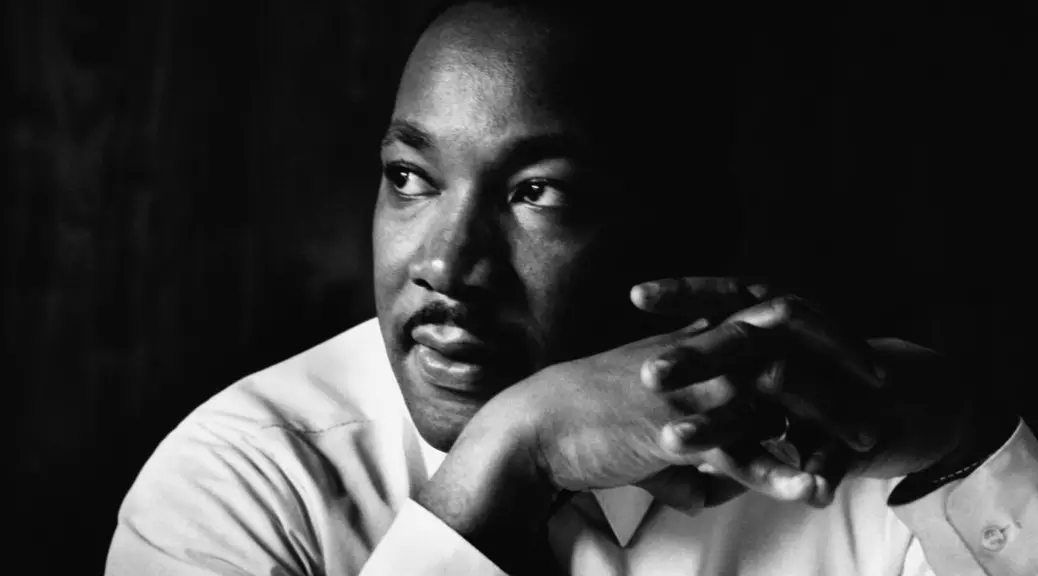

Writing from his holding cell at the Birmingham City Jail in April of 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. identified for his fellow clergymen what he was finding most perplexing during his fight against racial discrimination.

Though imprisoned for his role in organizing peaceful protests throughout Birmingham, Ala., where Jim Crow laws still enabled businessmen throughout the city to refuse service to black customers, Dr. King didn’t find the laws he was demonstrating against, nor the police force that enforced them, to be all that baffling.

Indeed, this was where the fight was, and when King counted the cost of launching an organized nonviolent campaign, imprisonment was among the first checks he was willing to write.

It wasn’t the humiliating signs and name-calling, nor the avowed racism of the Ku Klux Klan that most bothered Dr. King. His biggest disappointment was in what he called “the white moderate.”

“I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to ‘order; than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says, ‘I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action,’” he wrote.

“Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.”

Arrested April 12, Dr. King had reached a boiling point of sorts after a friend brought him a newspaper that included an op-ed co-signed by eight white Alabama pastors. Though they agreed with Dr. King in principle, they had written a letter publicly denouncing his methods of peaceful protest for which he was currently languishing in jail.

That was the spark that led Dr. King to respond in writing, pleading with his white fellow pastors to stand courageously with him in his respectful, yet determined path to see to it that all Americans be treated with equal dignity under the law.

Tweet This: It's our turn to stand for human dignity, whatever the cost. #prolife #MotivationMonday #MLKDay

But equality across racial lines was never going to happen as long as white church leaders remained silent, Dr. King argued. It was their time at bat, their turn to speak and to act in accordance with the truth of God’s Word—that He had created all men and women in His image, regardless of the color of their skin.

Such bold action was the heritage of the church, Dr. King reminded his fellow leaders. In past, the church had been “too God-intoxicated to be ‘astronomically intimidated.’ By their effort and example they brought an end to such ancient evils as infanticide and gladiatorial contests.” Yet, he lamented, “Things are different now.”

If the church were to fail to live up to its theology, Dr. King warned, it would “lose its authenticity, forfeit the loyalty of millions, and be dismissed as an irrelevant social club with no meaning for the twentieth century.”

Today, nearly 54 years after Dr. King wrote this letter, though the battle for racial equality has been largely won, the fight for racial harmony is still very much a work in process. As in Dr. King’s day, the larger society—whether they realize it or not—looks to the church to lead the way in racial reconciliation.

We have a transcendent message of a God who made us equally in His image (Gen. 1:27) and a Christ who has “broken down in his flesh the dividing wall of hostility” (Eph. 2:14) across racial and ethnic lines to make peace not only between God and man, but between man and man.

The good news we share is intended, ultimately, to magnify God’s infinite wisdom precisely by the uniting those who are racially, ethnically and culturally diverse under the common banner of faith in Christ. (Eph. 3:10, Rev. 7:9)

As Dr. King warned, should the church fail in her mission to speak God’s truth into crying needs of the day, we’ll leave a void that others will gladly fill through violence, bitterness and further division. As a society, we’re certainly seeing fruit of this in an ever-increasing hostility along racial lines throughout recent years, a point made clear by Dr. Mika Edmondson at The Gospel Coalition's 2016 conference.

It’s our duty and our delight, as the church, to call ourselves and our neighbors to what Dr. King labeled a “positive peace which is the presence of justice”. It’s our turn to strive toward a biblically formed, Spirit-empowered justice that only the good news of the Gospel can bring.

As fellow image-bearers of God, we’re simply not given the opportunity to remain silent or unengaged when our society assaults God’s image—whether through racism or in its more lethal forms such as gladiatorial contests, abortion, infanticide or euthanasia. All are assaults on God’s image-bearers and thus, assaults against God Himself. As such, the church has no right to be silent.

The question Dr. King posed to the white church 54 years ago rings just as urgent today: Will we act as a “thermometer that recorded the ideas and principles of popular opinion” or as a “thermostat that transformed the mores or society”?

Then and now, the choice is before us. Will we settle for "lukewarm acceptance" while our society assaults God's image-bearers, or are we "God-intoxicated" enough to be agents of change, no matter the cost?