Poland native Martin Arthur Couney used World’s Fairs and Great Exhibitions to save the lives of thousands of premature infants in Europe and America. At his exhibits, Couney showed that sequestering premature infants in an incubator ward could markedly reduce premature infant mortality. His method was clever, and he single-handedly increased the use of incubators in the US. Here is his story:

Reports have Couney studying medicine in Germany before working under Pierre Budin at the Paris Maternité Hospital in Paris, France. Budin himself was famed for establishing infant care facilities throughout Parisian hospitals and worked closely with Etienne Tarnier, the developer of one of the first infant warming devices. Thus, it was no surprise when Budin sent his protégé to the Berlin Exposition in 1896 to showcase the new “incubator” and promote its life-saving implementation throughout Europe.

[Click here to subscribe to Pregnancy Help News!]

The eugenics movement was in full swing as proponents reasoned that those prematurely delivered who were severely underdeveloped, sickly and/or malformed should be left for death. Dr. Harry Haiselden, of Chicago’s German-American Hospital, was a particularly extreme advocate for denying lifesaving treatment to infants he deemed “defective” and “undesirable.”

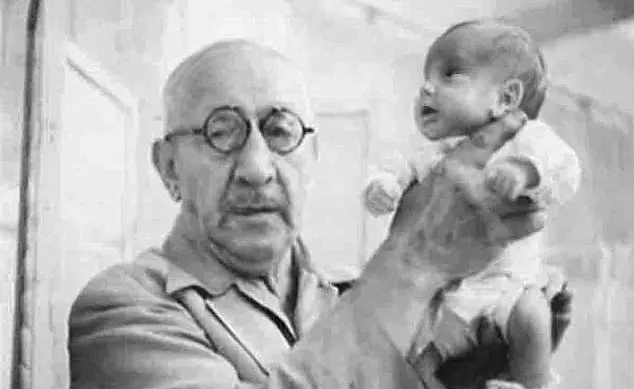

Couney called his first exhibit Kinderbrutanstalt -- the “child hatchery” -- and to his credit the blunt marketing worked. Couney obtained six premature infants from the director of Berlin’s Charité hospital, Rudolf Virchow, and kept his charges fully incubated while over 100,000 visitors paid to see them. After two months all six infants had survived.

Following the Berlin Exposition, Couney coordinated an infant incubator display for Great Britain’s 1897 Victorian Era Exhibition in London, England. Traveling with preemies from France, Couney transported the infants on a boat via the English Channel, in baskets with hot water bottles to keep them warm.

In 1898 Couney attempted to bring his show to the U.S. Midwest but the rural location failed to attract crowds. In 1901 he returned for the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. Here he housed the infants in the “amusement” section rather than the science building, garnering public and medical press. Following the Exposition, the Children’s Hospital of Buffalo bought several infant incubators.

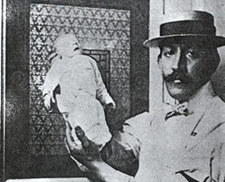

Five years later, Couney immigrated to the United States and opened a permanent exhibit of infant incubators at Coney Island in Brooklyn, New York. “Infant Incubators with Real Babies -- Once Seen Never Forgotten” read one queue sign. “Life Begins at the Baby Incubator,” read another.

Couney treated premature infants of parents who could not afford proper medical care and kept the names of his tiny patients anonymous. He did not bill the parents for care, instead charging the public an admission fee of 25 cents. Couney employed five wet-nurses to feed the infants and fifteen highly trained medical technicians, including his daughter, who was a nurse. He required the wet-nurses to keep a strict diet because of their role in treatment of premature infants. Although the exhibit was located in an amusement park, the atmosphere inside was solemn and professional.

As news of Couney's ingenious care and remarkable results spread, it wasn’t uncommon for desperate parents to bring their tiny newborns to Couney wrapped in towels or boxes, often rushing from hospitals where they were told the babies would die. One such case is described in the Daily Mail’s post:

Two women gave birth in July 1937 to premature sets of twins in a New York hospital, all four babies so small that their chances of survival were slim. Neonatal medicine was still relatively primitive in America, and the hospital had only one incubator – which was already in use for another child.

The doctor gave both mothers an option: They could send their babies to the amusement park at Coney Island – of all places – where a ‘doctor’ was exhibiting preemies in incubators, a stone’s throw from freak shows and all manner of curiosities as people paid 25 cents to see the tiny humans. While the babies convalesced under the watchful eye of nurses, leopards and elephants paraded nearby, aquarium shows drew spectators and strippers gyrated for paying customers.

One new mother, horrified, refused to exhibit her newborns in such a carnival atmosphere. The other, desperate, immediately agreed, grabbing at any shred of hope that someone could save her two-and-a-half-pound daughter and her three-pound son.

And that’s exactly what happened. Norma Johnson and her twin brother, George, survived in Coney Island and went on to live long and full lives, welcoming nine children and 13 grandchildren between them. The other preemie twins – the boys kept in the hospital – both died.

Also from the Daily Mail report:

Lucille Conlin Horn was brought in a taxi by her father to Couney's Atlantic City sideshow after her twin perished; the doctor had warned her parents she'd likely die too, but they didn't accept this. She lived until age 96 and passed in 2017.

Couney maintained two exhibits in Coney Island, one in Luna Park from 1903 until 1943, and another in Dreamland from 1904 until the fire of 1911. The babies were saved from the fire by Coney Island’s “human marvels” — the people society and amusement parks labeled freaks.

He also continued to tour with his infant incubator exhibit around the country to other amusement parks and fairs, but not without constant criticism. There were numerous attempts to shut down his exhibits, which many considered to be “against maternal nature.”

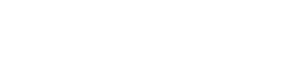

But Couney persisted and provided medical care for the children of parents otherwise unable to afford it. By 1939, Couney had treated more than 8,000 premature babies, with reportedly more than 6,500 surviving. One of them was his daughter, Hildegarde, who had weighed less than three pounds at birth.

The nurse in the center is Couney's daughter, Hildegarde, who died in 1956/Neontaology.org

By the time his Luna Park exhibit closed in 1943 due to low popularity and revenue, Couney's methods had begun to be utilized in conventional hospitals. Couney retired shortly after closing the exhibit and died alone at his home in Sea Gate on Coney Island in 1950.

Couney’s legacy reaches far wider than his organized and immediate care. During his life, he continued to share his medical and scientific knowledge with willing hospitals. An example was the “blindness” cases of early incubators, in particular Katherine Ashe Meyer. Her hospital had called in her parents nine years after Couney had incubated her. They said to her father, “There is something we don’t understand. All the babies that were in our incubators are going blind – but your baby’s eyes are good.”

Couney’s work was acknowledged by Dr. Julian Hess, often regarded the father of American neonatology, according the Daily Mail report, with Hess thanking Couney in his 1922 book about premature babies.

Tweet This: Couney’s work was recognized by Dr. Julian Hess, who is known as the father of American neonatology.

For more information on Couney’s efforts, check out Dawn Raffel’s book, The Strange Case of Dr. Couney and Claire Prentice’s FREE read, Miracle at Coney Island: How a Sideshow Doctor Saved Thousands of Babies and Transformed American Medicine. You can also stay tuned for the upcoming feature film, Dreamland, produced by Nash Entertainment, and listen to 99% Invisible’s researched podcast episode.

Editor's note: Elements of Martin Couney's background and his credentials are the subject of some question. Multiple sources report that he was never actually qualified as a medical doctor. While his work was highly unconventional, he saved thousands of babies, with the Smithsonian Magazine stating in a report that, "the results are unimpeachable," and Couney has regard as a pioneer of American neonatology.